Panama - Introduction

Panama (officially: Republic of Panama) is a country in Americas, precisely in Central America, with a population of about 4.5 Millions inhabitants today (2024-06-23). The capital city of Republic of Panama is Panama City, and the official country TLD code is .pa. Panama has cca2, cca3, cioc, ccn3 codes as PA, PAN, PAN, 591 respectively. Check some other vital information below.

Panama , Coat of Arms

Names

| Common | Panama |

|---|---|

| Official | Republic of Panama |

| Common (Native) | Panama |

| Official (Native) | Republic of Panama |

| Alternative spellings | PA, Republic of Panama, República de Panamá |

| Translations ⬇️ | |

Languages

| spa | Spanish |

|---|

Geography

Panama is located in Central America and has a total land area of 75417 km². It is bounded by Colombia, Costa Rica and the capital city is Panama City

| Region/Continent | North America |

|---|---|

| Subregion | Central America |

| TimeZone | UTC-05:00 |

| Capital city | Panama City |

| Area | 75417 km² |

| Population 2024-06-23 | 4.5 Millions |

| Bordered Countreies | Colombia, Costa Rica |

| Demonym | |

| eng | Male: Panamanian / Female: Panamanian |

| fra | Male: Panaméen / Female: Panaméenne |

| Lat/Lng | 9, -80 |

Historical data and more

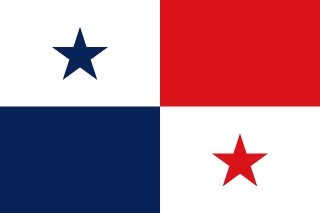

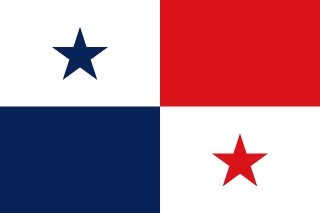

The National Flag of Panama

The flag of Panama is composed of four equal rectangular areas — a white rectangular area with a blue five-pointed star at its center, a red rectangular area, a white rectangular area with a red five-pointed star at its center, and a blue rectangular area — in the upper hoist side, upper fly side, lower fly side and lower hoist side respectively.

Historyedit

This section needs additional citations for verification. (October 2017) |

Pre-Columbian periodedit

The Isthmus of Panama was formed about three million years ago when the land bridge between North and South America finally became complete, and plants and animals gradually crossed it in both directions. The existence of the isthmus affected the dispersal of people, agriculture and technology throughout the American continent from the appearance of the first hunters and collectors to the era of villages and cities.

The earliest discovered artifacts of indigenous peoples in Panama include Paleo-Indian projectile points. Later central Panama was home to some of the first pottery-making in the Americas, for example the cultures at Monagrillo, which date back to 2500–1700 BC. These evolved into significant populations best known through their spectacular burials (dating to c. 500–900 AD) at the Monagrillo archaeological site, and their Gran Coclé style polychrome pottery. The monumental monolithic sculptures at the Barriles (Chiriqui) site are also important traces of these ancient isthmian cultures.

Before Europeans arrived Panama was widely settled by Chibchan, Chocoan, and Cueva peoples. The largest group were the Cueva (whose specific language affiliation is poorly documented). The size of the indigenous population of the isthmus at the time of European colonization is uncertain. Estimates range as high as two million people, but more recent studies place that number closer to 200,000. Archaeological finds and testimonials by early European explorers describe diverse native isthmian groups exhibiting cultural variety and suggesting people developed by regular regional routes of commerce. Austronesians had a trade network to Panama as there is evidence of coconuts reaching the Pacific coast of Panama from the Philippines in Precolumbian times.

When Panama was colonized, the indigenous peoples fled into the forest and nearby islands. Scholars believe that infectious disease was the primary cause of the population decline of American natives. The indigenous peoples had no acquired immunity to diseases such as smallpox which had been chronic in Eurasian populations for centuries.

Conquest to 1799edit

Rodrigo de Bastidas sailed westward from Venezuela in 1501 in search of gold, and became the first European to explore the isthmus of Panama. A year later, Christopher Columbus visited the isthmus, and established a short-lived settlement in the province of Darien. Vasco Núñez de Balboa's tortuous trek from the Atlantic to the Pacific in 1513 demonstrated that the isthmus was indeed the path between the seas, and Panama quickly became the crossroads and marketplace of Spain's empire in the New World. King Ferdinand II assigned Pedro Arias Dávila as Royal Governor. He arrived in June 1514 with a 19 vessels and 1,500 men. In 1519, Dávila founded Panama City. Gold and silver were brought by ship from South America, hauled across the isthmus, and loaded aboard ships for Spain. The route became known as the Camino Real, or Royal Road, although it was more commonly known as Camino de Cruces (Road of Crosses) because of the number of gravesites along the way. At 1520 the Genoese controlled the port of Panama. The Genoese obtained a concession from the Spanish to exploit the port of Panama mainly for the slave trade, until the destruction of the primeval city in 1671. In the meantime in 1635 Don Sebastián Hurtado de Corcuera, the then governor of Panama, had recruited Genoese, Peruvians, and Panamanians, as soldiers to wage war against Muslims in the Philippines and to found the city of Zamboanga.

Panama was under Spanish rule for almost 300 years (1538–1821), and became part of the Viceroyalty of Peru, along with all other Spanish possessions in South America. From the outset, Panamanian identity was based on a sense of "geographic destiny", and Panamanian fortunes fluctuated with the geopolitical importance of the isthmus. The colonial experience spawned Panamanian nationalism and a racially complex and highly stratified society, the source of internal conflicts that ran counter to the unifying force of nationalism.

In 1538, the Real Audiencia of Panama was established, initially with jurisdiction from Nicaragua to Cape Horn, until the conquest of Peru. A Real Audiencia was a judicial district that functioned as an appeals court. Each audiencia had an oidor (Spanish: hearer, a judge).

Spanish authorities had little control over much of the territory of Panama. Large sections managed to resist conquest and missionization until very late in the colonial era. Because of this, indigenous people of the area were often referred to as "indios de guerra" (war Indians) who resisted Spanish attempts to conquer them or missionize them. However, Panama was enormously important to Spain strategically because it was the easiest way to transship silver mined in Peru to Europe. Silver cargoes were landed on the west coast of Panama and then taken overland to Portobello or Nombre de Dios on the Caribbean side of the isthmus for further shipment. Aside from the European route, there was also an Asian-American route, which led to traders and adventurers carrying silver from Peru going over land through Panama to reach Acapulco, Mexico before sailing to Manila, Philippines using the famed Manila Galleons. In 1579, the royal monopoly that Acapulco, Mexico had on trading with Manila, Philippines was relaxed and Panama was assigned as another port that was able to trade directly with Asia.

Because of incomplete Spanish control, the Panama route was vulnerable to attack from pirates (mostly Dutch and English), and from "new world" Africans called cimarrons who had freed themselves from enslavement and lived in communes or palenques around the Camino Real in Panama's Interior, and on some of the islands off Panama's Pacific coast. One such famous community amounted to a small kingdom under Bayano, which emerged in the 1552 to 1558 period. Sir Francis Drake's famous raids on Panama in 1572–73 and John Oxenham's crossing to the Pacific Ocean were aided by Panama cimarrons, and Spanish authorities were only able to bring them under control by making an alliance with them that guaranteed their freedom in exchange for military support in 1582.

The following elements helped define a distinctive sense of autonomy and of regional or national identity within Panama well before the rest of the colonies: the prosperity enjoyed during the first two centuries (1540–1740) while contributing to colonial growth; the placing of extensive regional judicial authority (Real Audiencia) as part of its jurisdiction; and the pivotal role it played at the height of the Spanish Empire – the first modern global empire.

The end of the encomienda system in Azuero, however, sparked the conquest of Veraguas in that same year. Under the leadership of Francisco Vázquez, the region of Veraguas passed into Castilian rule in 1558. In the newly conquered region, the old system of encomienda was imposed. On the other hand, the Panamanian movement for independence can be indirectly attributed to the abolition of the encomienda system in the Azuero Peninsula, set forth by the Spanish Crown, in 1558 because of repeated protests by locals against the mistreatment of the native population. In its stead, a system of medium and smaller-sized landownership was promoted, thus taking away the power from the large landowners and into the hands of medium and small-sized proprietors.

Panama was the site of the ill-fated Darien scheme, which set up a Scottish colony in the region in 1698. This failed for a number of reasons, and the ensuing debt contributed to the union of England and Scotland in 1707.

In 1671, the privateer Henry Morgan, licensed by the English government, sacked and burned the city of Panama – the second most important city in the Spanish New World at the time. In 1717 the viceroyalty of New Granada (northern South America) was created in response to other Europeans trying to take Spanish territory in the Caribbean region. The Isthmus of Panama was placed under its jurisdiction. However, the remoteness of New Granada's capital, Santa Fe de Bogotá (the modern capital of Colombia) proved a greater obstacle than the Spanish crown anticipated as the authority of New Granada was contested by the seniority, closer proximity, and previous ties to the viceroyalty of Peru and even by Panama's own initiative. This uneasy relationship between Panama and Bogotá would persist for centuries.

In 1744, Bishop Francisco Javier de Luna Victoria DeCastro established the College of San Ignacio de Loyola and on June 3, 1749, founded La Real y Pontificia Universidad de San Javier. By this time, however, Panama's importance and influence had become insignificant as Spain's power dwindled in Europe and advances in navigation technique increasingly permitted ships to round Cape Horn in order to reach the Pacific. While the Panama route was short it was also labor-intensive and expensive because of the loading and unloading and laden-down trek required to get from the one coast to the other.

1800sedit

As the Spanish American wars of independence were heating up all across Latin America, Panama City was preparing for independence; however, their plans were accelerated by the unilateral Grito de La Villa de Los Santos (Cry From the Town of Saints), issued on November 10, 1821, by the residents of Azuero without backing from Panama City to declare their separation from the Spanish Empire. In both Veraguas and the capital this act was met with disdain, although on differing levels. To Veraguas, it was the ultimate act of treason, while to the capital, it was seen as inefficient and irregular, and furthermore forced them to accelerate their plans.

Nevertheless, the Grito was a sign, on the part of the residents of Azuero, of their antagonism toward the independence movement in the capital. Those in the capital region in turn regarded the Azueran movement with contempt, since the separatists in Panama City believed that their counterparts in Azuero were fighting not only for independence from Spain, but also for their right to self-rule apart from Panama City once the Spaniards were gone.

It was seen as a risky move on the part of Azuero, which lived in fear of Colonel José Pedro Antonio de Fábrega y de las Cuevas (1774–1841). The colonel was a staunch loyalist and had all of the isthmus' military supplies in his hands. They feared quick retaliation and swift retribution against the separatists.

What they had counted on, however, was the influence of the separatists in the capital. Ever since October 1821, when the former Governor General, Juan de la Cruz Murgeón, left the isthmus on a campaign in Quito and left a colonel in charge, the separatists had been slowly converting Fábrega to the separatist side. So, by November 10, Fábrega was now a supporter of the independence movement. Soon after the separatist declaration of Los Santos, Fábrega convened every organization in the capital with separatist interests and formally declared the city's support for independence. No military repercussions occurred because of skillful bribing of royalist troops.

Post-colonial Panamaedit

In the 80 years following independence from Spain, Panama was a subdivision of Gran Colombia, after voluntarily joining the country at the end of 1821. It then became part of the Republic of New Granada in 1831 and was divided into several provinces. In 1855, the autonomous State of Panama was created within the Republic out of the New Granada provinces of Panama, Azuero, Chiriquí, and Veraguas. It continued as a state in the Granadine Confederation (1858–1863) and United States of Colombia (1863–1886). The 1886 constitution of the modern Republic of Colombia created a new Panama Department.

The people of the isthmus made over 80 attempts to secede from Colombia. They came close to success in 1831, then again during the Thousand Days' War of 1899–1902, understood among indigenous Panamanians as a struggle for land rights under the leadership of Victoriano Lorenzo.

The US intent to influence the area, especially the Panama Canal's construction and control, led to the separation of Panama from Colombia in 1903 and its establishment as a nation. When the Senate of Colombia rejected the Hay–Herrán Treaty on January 22, 1903, the United States decided to support and encourage the Panamanian separatist movement.

In November 1903 Panama, tacitly supported by the United States, proclaimed its independence and concluded the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty with the United States without the presence of a single Panamanian. Philippe Bunau-Varilla, a French engineer and lobbyist represented Panama even though Panama's president and a delegation had arrived in New York to negotiate the treaty. The treaty was quickly drafted and signed the night before the Panamanian delegation arrived in Washington. Mr. Bunau-Varilla was in the employ of the French Canal company that had failed and was now bankrupt. The treaty granted rights to the United States "as if it were sovereign" in a zone roughly 16 km (10 mi) wide and 80 km (50 mi) long. In that zone, the US would build a canal, then administer, fortify, and defend it "in perpetuity".

In 1914 the United States completed the existing 83-kilometer-long (52-mile) canal.

Because of the strategic importance of the canal during World War II, the US extensively fortified access to it.

From 1903 to 1968, Panama was a constitutional democracy dominated by a commercially oriented oligarchy. During the 1950s, the Panamanian military began to challenge the oligarchy's political hegemony. The early 1960s saw also the beginning of sustained pressure in Panama for the renegotiation of the Hay–Bunau-Varilla Treaty, including riots that broke out in early 1964, resulting in widespread looting and dozens of deaths, and the evacuation of the American embassy.

Amid negotiations for the Robles–Johnson treaty, Panama held elections in 1968. The candidates were:

- Dr. Arnulfo Arias Madrid, Unión Nacional (National Union)

- Antonio González Revilla, Democracia Cristiana (Christian Democrats)

- Engr. David Samudio, Alianza del Pueblo (People's Alliance), who had the government's support.

Arias Madrid was declared the winner of elections that were marked by violence and accusations of fraud against Alianza del Pueblo. On October 1, 1968, Arias Madrid took office as president of Panama, promising to lead a government of "national union" that would end the reigning corruption and pave the way for a new Panama. A week and a half later, on October 11, 1968, the National Guard (Guardia Nacional) ousted Arias and initiated the downward spiral that would culminate with the United States' invasion in 1989. Arias, who had promised to respect the hierarchy of the National Guard, broke the pact and started a large restructuring of the Guard. To preserve the Guard's and his vested interests, Lieutenant Colonel Omar Torrijos Herrera and Major Boris Martínez commanded another military coup against the government.

The military justified itself by declaring that Arias Madrid was trying to install a dictatorship, and promised a return to constitutional rule. In the meantime, the Guard began a series of populist measures that would gain support for the coup. Among them were:

- Price freezing on food, medicine and other goods until January 31, 1969

- rent level freeze

- legalization of the permanence of squatting families in boroughs surrounding the historic site of Panama Viejo

Parallel to this, the military began a policy of repression against the opposition, who were labeled communists. The military appointed a Provisional Government Junta that was to arrange new elections. However, the National Guard would prove to be very reluctant to abandon power and soon began calling itself El Gobierno Revolucionario (The Revolutionary Government).

Post-1970edit

Under Omar Torrijos's control, the military transformed the political and economic structure of the country, initiating massive coverage of social security services and expanding public education.

The constitution was changed in 1972. To reform the constitution, the military created a new organization, the Assembly of Corregimiento Representatives, which replaced the National Assembly. The new assembly, also known as the Poder Popular (Power of the People), was composed of 505 members selected by the military with no participation from political parties, which the military had eliminated. The new constitution proclaimed Omar Torrijos as the Maximum Leader of the Panamanian Revolution, and conceded him unlimited power for six years, although, to keep a façade of constitutionality, Demetrio B. Lakas was appointed president for the same period.

In 1981, Torrijos died in a plane crash. Torrijos' death altered the tone of Panama's political evolution. Despite the 1983 constitutional amendments which proscribed a political role for the military, the Panama Defense Force (PDF), as they were then known, continued to dominate Panamanian political life. By this time, General Manuel Antonio Noriega was firmly in control of both the PDF and the civilian government.

In the 1984 elections, the candidates were:

- Nicolás Ardito Barletta Vallarino, supported by the military in a union called UNADE

- Arnulfo Arias Madrid, for the opposition union ADO

- ex-General Rubén Darío Paredes, who had been forced to an early retirement by Manuel Noriega, running for the Partido Nacionalista Popular (PAP; "Popular Nationalist Party")

- Carlos Iván Zúñiga, running for the Partido Acción Popular (PAPO; Popular Action Party)

Barletta was declared the winner of elections that had been considered to be fraudulent. Barletta inherited a country in economic ruin and hugely indebted to the International Monetary Fund and the World Bank. Amid the economic crisis and Barletta's efforts to calm the country's creditors, street protests arose, and so did military repression.

Meanwhile, Noriega's regime had fostered a well-hidden criminal economy that operated as a parallel source of income for the military and their allies, providing revenues from drugs and money laundering. Toward the end of the military dictatorship, a new wave of Chinese migrants arrived on the isthmus in the hope of migrating to the United States. The smuggling of Chinese became an enormous business, with revenues of up to 200 million dollars for Noriega's regime (see Mon 167).

The military dictatorship assassinated or tortured more than one hundred Panamanians and forced at least a hundred more dissidents into exile. (see Zárate 15). Noriega's regime was supported by the United States and it began playing a double role in Central America. While the Contadora group, an initiative launched by the foreign ministers of various Latin American nations including Panama's, conducted diplomatic efforts to achieve peace in the region, Noriega supplied Nicaraguan Contras and other guerrillas in the region with weapons and ammunition on behalf of the CIA.

On June 6, 1987, the recently retired Colonel Roberto Díaz Herrera, resentful that Noriega had broken the agreed-upon "Torrijos Plan" of succession that would have made him the chief of the military after Noriega, decided to denounce the regime. He revealed details of electoral fraud, accused Noriega of planning Torrijos's death and declared that Torrijos had received 12 million dollars from the Shah of Iran for giving the exiled Iranian leader asylum. He also accused Noriega of the assassination by decapitation of then-opposition leader, Dr. Hugo Spadafora.

On the night of June 9, 1987, the Cruzada Civilista ("Civic Crusade") was created and began organizing actions of civil disobedience. The Crusade called for a general strike. In response, the military suspended constitutional rights and declared a state of emergency in the country. On July 10, the Civic Crusade called for a massive demonstration that was violently repressed by the "Dobermans", the military's special riot control unit. That day, later known as El Viernes Negro ("Black Friday"), left many people injured and killed.

United States President Ronald Reagan began a series of sanctions against the military regime. The United States froze economic and military assistance to Panama in the middle of 1987 in response to the domestic political crisis in Panama and an attack on the US embassy. The sanctions failed to oust Noriega, but severely hurt Panama's economy. Panama's gross domestic product (GDP) declined almost 25 percent between 1987 and 1989.

On February 5, 1988, General Manuel Antonio Noriega was accused of drug trafficking by federal juries in Tampa and Miami. Human Rights Watch wrote in its 1989 report: "Washington turned a blind eye to abuses in Panama for many years until concern over drug trafficking prompted indictments of the general [Noriega] by two grand juries in Florida in February 1988".

In April 1988, US President Ronald Reagan invoked the International Emergency Economic Powers Act, freezing Panamanian government assets in all US organizations. In May 1989 Panamanians voted overwhelmingly for the anti-Noriega candidates. The Noriega regime promptly annulled the election and embarked on a new round of repression.

US invasion (1989)edit

The United States invaded Panama on December 20, 1989, codenamed Operation Just Cause. The U.S. stated the operation was "necessary to safeguard the lives of U.S. citizens in Panama, defend democracy and human rights, combat drug trafficking, and secure the neutrality of the Panama Canal as required by the Torrijos–Carter Treaties". The US reported 23 servicemen killed and 324 wounded, with the number of Panamanian soldiers killed estimated at 450. The estimates for civilians killed in the conflict ranges from 200 to 4,000. The United Nations put the Panamanian civilian death toll at 500, Americas Watch estimated 300, the United States gave a figure of 202 civilians killed and former US attorney general Ramsey Clark estimated 4,000 deaths. It represented the largest United States military operation since the Vietnam War. The number of US civilians (and their dependents), who had worked for the Panama Canal Commission and the US military, and were killed by the Panamanian Defense Forces, has never been fully disclosed.

On December 29, the United Nations General Assembly approved a resolution calling the intervention in Panama a "flagrant violation of international law and of the independence, sovereignty and territorial integrity of the States". A similar resolution was vetoed in the Security Council by the United States, the United Kingdom, and France. Noriega was captured and flown to Miami to be tried. The conflict ended on January 31, 1990.

The urban population, many living below the poverty level, was greatly affected by the 1989 intervention. As pointed out in 1995 by a UN Technical Assistance Mission to Panama, the fighting displaced 20,000 people. The most heavily affected district was the El Chorrillo area of Panama City, where several blocks of apartments were completely destroyed. The economic damage caused by the fighting has been estimated at between 1.5 and 2 billion dollars. Most Panamanians supported the intervention.

Post-intervention eraedit

Panama's Electoral Tribunal moved quickly to restore civilian constitutional government, reinstated the results of the May 1989 election on December 27, 1989, and confirmed the victory of President Guillermo Endara and Vice Presidents Guillermo Ford and Ricardo Arias Calderón.

During its five-year term, the often-fractious government struggled to meet the public's high expectations. Its new police force was a major improvement over its predecessor but was not fully able to deter crime. Ernesto Pérez Balladares was sworn in as president on September 1, 1994, after an internationally monitored election campaign.

On September 1, 1999, Mireya Moscoso, the widow of former President Arnulfo Arias Madrid, took office after defeating PRD candidate Martín Torrijos, son of Omar Torrijos, in a free and fair election. During her administration, Moscoso attempted to strengthen social programs, especially for child and youth development, protection, and general welfare. Moscoso's administration successfully handled the Panama Canal transfer and was effective in the administration of the Canal.

The PRD's Martin Torrijos won the presidency and a legislative majority in the National Assembly in 2004. Torrijos ran his campaign on a platform of, among other pledges, a "zero tolerance" for corruption, a problem endemic to the Moscoso and Perez Balladares administrations. After taking office, Torrijos passed a number of laws which made the government more transparent. He formed a National Anti-Corruption Council whose members represented the highest levels of government and civil society, labor organizations, and religious leadership. In addition, many of his closest Cabinet ministers were non-political technocrats known for their support for the Torrijos government's anti-corruption aims. Despite the Torrijos administration's public stance on corruption, many high-profile cases, particularly involving political or business elites, were never acted upon.

Conservative supermarket magnate Ricardo Martinelli was elected to succeed Martin Torrijos with a landslide victory in the May 2009 Panamanian general election. Martinelli's business credentials drew voters worried by slowing growth during the Great Recession. Standing for the four-party opposition Alliance for Change, Martinelli gained 60 percent of the vote, against 37 percent for the candidate of the governing left-wing Democratic Revolutionary Party (PRD).

On May 4, 2014, Vice President Juan Carlos Varela, candidate of the Partido Panamenista (Panamanian Party) won the 2014 presidential election with over 39 percent of the votes, against the party of his former political partner Ricardo Martinelli, Cambio Democrático, and their candidate José Domingo Arias. He was sworn in on July 1, 2014. On July 1, 2019 Laurentino Cortizo took possession of the presidency. Cortizo was the candidate of Democratic Revolution Party (PRD) in the May 2019 presidential election.

During the presidency of Cortizo, numerous events happened in the country, including the COVID-19 pandemic and its economic impact, and the 2022 and 2023 protests.

| Currency | |

|---|---|

| Name | United States dollar |

| Code | USD |

| Symbol | $ |

| Other info | |

| Idependent | yes, officially-assigned |

| UN Member country | yes |

| Start of Week | monday |

| Car Side | right |

| Codes | |

| ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 | PA |

| ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 | PAN |

| ISO 3166-1 numeric | 591 |

| International calling code | +507 |

| FIFA 3 Letter Code | PAN |

All Important Facts about Panama

Want to know more about Panama? Check all different factbooks for Panama below.