Dominican Republic - Introduction

Dominican Republic (officially: Dominican Republic) is a country in Americas, precisely in Caribbean, with a population of about 11.5 Millions inhabitants today (2025-04-01). The capital city of Dominican Republic is Santo Domingo, and the official country TLD code is .do. Dominican Republic has cca2, cca3, cioc, ccn3 codes as DO, DOM, DOM, 214 respectively. Check some other vital information below.

Dominican Republic , Coat of Arms

Names

| Common | Dominican Republic |

|---|---|

| Official | Dominican Republic |

| Common (Native) | Dominican Republic |

| Official (Native) | Dominican Republic |

| Alternative spellings | DO |

| Translations ⬇️ | |

Languages

| spa | Spanish |

|---|

Geography

Dominican Republic is located in Caribbean and has a total land area of 48671 km². It is bounded by Haiti and the capital city is Santo Domingo

| Region/Continent | North America |

|---|---|

| Subregion | Caribbean |

| TimeZone | UTC-04:00 |

| Capital city | Santo Domingo |

| Area | 48671 km² |

| Population 2025-04-01 | 11.5 Millions |

| Bordered Countreies | Haiti |

| Demonym | |

| eng | Male: Dominican / Female: Dominican |

| fra | Male: Dominicain / Female: Dominicaine |

| Lat/Lng | 19, -70.66666666 |

Historical data and more

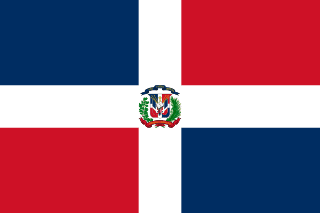

The National Flag of Dominican Republic

The flag of the Dominican Republic is divided into four rectangles by a centered white cross that extends to the edges of the field and bears the national coat of arms in its center. The upper hoist-side and lower fly-side rectangles are blue and the lower hoist-side and upper fly-side rectangles are red.

| Currency | |

|---|---|

| Name | Dominican peso |

| Code | DOP |

| Symbol | $ |

| Other info | |

| Idependent | yes, officially-assigned |

| UN Member country | yes |

| Start of Week | monday |

| Car Side | right |

| Codes | |

| ISO 3166-1 alpha-2 | DO |

| ISO 3166-1 alpha-3 | DOM |

| ISO 3166-1 numeric | 214 |

| International calling code | +1 |

| FIFA 3 Letter Code | DOM |

All Important Facts about Dominican Republic

Want to know more about Dominican Republic? Check all different factbooks for Dominican Republic below.